Preparing a silk yarn (Sand Dune) for dye and how to shift a dye shade

Featuring: Sand Dune 52% Mulberry Silk, 24% Superkid Mohair, 20% Fine Merino Wool, 4% Viscose

Our Goal: Learn about the characteristics of dyeing a silk based yarn and how to shift a shade between two colors.

Abstract: Today I’ll show you how to prep and dye a silk-based yarn, how to properly prepare it to receive the dye, as well as why a dye might break into it’s component colors. We also cover how to find a shade in between two dye pigments for color matching and multi process dye application to preserve the microtonality of dye pigments that break. For those with time to read the finer details, let’s dive in!

YOU WILL NEED:

- 3 Skeins of Sand Dune from Knomad

- Gloves

- Respirator

- A way to heat set your yarn (steamer, proofer, oven, induction plate)

- Acid-Reactive Dye from Pro Chem Washfast Acid in Lobster Bisque and Reddish Brown

- 8” deep stainless steel restaurant tray

- Citric Acid

- Gram Scale

- Synthrapol textile detergent

Fill an 8” deep steel tray with 6” warm water, 1 teaspoon Synthrapol and 2 teaspoons citric acid, then soak the skeins in the tray overnight. You’ll know they’re properly wetted out when they aren’t floating on the surface and there’s no bright white patches of dry silk streaked through the yarn.

WHAT IS SYNTHRAPOL (FROM WWW.PROCHEMICALANDDYE.NET)

A concentrated liquid wetting agent and surfactant compatible with all dye classifications. May also be added to the dye bath to add levelness and aid in wetting out the fiber.

- Will remove excess dye from hand dyed fabrics.

- Will remove sizing from fabric before dyeing.

- Use in the dye bath for even color.

- A concentrated wetting agent, known as a surfactant.

Since silk takes a very long time to wet with just water, we use Synthrapol to help drive the water into the tightly woven silk fibers so that the dye can penetrate deeply and evenly. Skipping this step ensures that you will have patchy white spaces that resist the dye throughout the skein. Quick note: Do not use a dish detergent instead of Synthrapol. Dish detergent will change the Ph of the water such that the dye won’t bind securely (if at all).

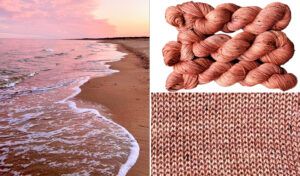

The color we’re going for is this beautiful rosewood, like the way the sunset reflects the light on the sand in our reference image. How do we go about recreating this color? We pick the two closest colors and adjust the saturation point of each, then dye each color in a separate pass to preserve the way the dye breaks and the individual characteristics of each color.

The two shades I felt most closely represented this color are Lobster Bisque and Reddish Brown. Reddish Brown doesn’t have the rosy pink, and Lobster Bisque is missing the warm brown notes.

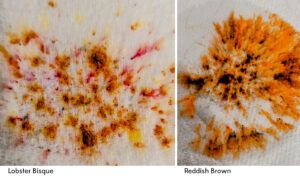

These particular dyes are not primaries (pure pigments) but a blend of a bunch of different colors. If you wet out a paper towel and sprinkle the smallest amount of dye, you can catch a glimpse of the basis of these colors and see how they’re likely to break on the yarn.

Dye

1.5% d.o.s. (degree of strength per weight of goods) Lobster Bisque

0.5% d.o.s. (degree of strength per weight of goods) Reddish Brown

3 skeins of Sand Dune: 300 grams x 1.5% = 4.5 grams of Lobster Bisque

300 grams x .5% = 1.5 grams of Reddish Brown

Process

Dissolve 4.5 grams Lobster Bisque in 2 gallons of water. Gently lower the pre-wetted skeins into the dye bath and make sure they’re fully saturated. Let sit for 4 hours. Bring up to 210 degrees Fahrenheit (just below a boil) for 30 minutes.

After the Lobster Bisque has cleared, lift the skeins out and pour in your well dissolved Reddish Brown stock (500 ML hot water and 1.5 grams Reddish Brown Dye) . Make sure there’s no clumps or chunks, as this will give very uneven results and dark patches. Submerge your skeins and let sit at 210 Fahrenheit for an additional 15 minutes, then take your tray off the heat and let cool to room temperature.

Why do we dye them separately, instead of mixing all the stock together and heat setting right away? Well, at Thanksgiving dinner, you could mix the mashed potatoes, peas, turkey, gravy, stuffing and pie together to serve the food more efficiently from a giant mound. But the individual notes and flavors of the food would be lost, or even cancel each other out.

The same goes for how the pigments used in dyeing interact differently if they’re all mixed together cold, as opposed to a layered approach. The resulting color would be missing all those little micro tones from the dye splitting. And there wouldn’t be that hazy aura of color from dyeing them separately.

That’s why we didn’t use equal amounts of Lobster Bisque and Reddish Brown. Lobster Bisque is a far less saturated color than Reddish Brown. So we had to dial the Reddish Brown back to ⅓ the saturation and dye the Lobster Bisque first to preserve the unique flavors both colors bring to the yarn. Those tiny dots of pink, yellow and blue are what bring a richness, complexity and depth of color that make the skein so attractive.

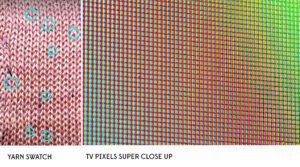

See all those tiny blue dots? It’s one of the components of the dye striking separately. I think of it as the same as when you were a kid and put your eyeball next to the TV screen and everything became a mix of red, yellow and blue pixels. Any dye that’s not a primary is just a mix of red, yellow and blue in very precise ratios (and a filler material that changes the color value from rich to pastel)

While I’m not a chemist and thus can’t answer for exactly why this is happening, my research on pigment molecules suggests that some of the colors used are striking (adhering to the yarn) in different temperature ranges. So the red, pink and yellow components adhered more or less at the same time, probably in a narrow temperature range, while the blue struck in a different temperature range, which resulted in its solitary unmixed appearance in our yarn.

I hope you enjoyed learning about silk, layering dyes, and the fun ways that dyes break when they’re not primaries. Till next time!

Nic